‘Despite currency recovery, we expect Sales to decline further’

‘Surplus dollar liquidity triggered a surge. Spread widens’

‘ABC company’s transactions are on hold. XYZ who is the main vendor for ABC is being sued for anti-competitive conduct’

‘Is the tail risk event an indication of further downfall across the industry?’

We hear these news captions very often. Only with mild variances, shuffle of words and in different contexts. But, how far are you able to apprehend the underlying impact that each event could cause? Can you always tell if two events are correlated? More importantly, can you distinguish opportunities from threats while investing?

Understanding some of the illusions and fallacies in Finance will help you grasp the market eccentricities better and provides a clear sight for dealing with investment opportunities and threats.

Theories and assumptions

There are various theories proposed in the past which attempt at quantifying risk and returns based on a list of underlying assumptions. We can take Capital Asset Pricing model and Modigliani – Miller model, for example.

Both the theories are based on assumptions like rational behaviour, no taxes or transaction costs, everyone has access to the same type of information, etc., that are unrealistic in regular, day-to-day market scenarios.

While theories were a great head-start in quantifying future anticipated risks and returns, most of them can only be considered the initial and primary step in perpetually fine-tuning the return- and risk-based models.

No theory can, as is stand through the test of time, especially in our pervasively dynamic market environment. Every boom and bust event leaves us with large key takeaways but no two events are ever the same.

Here are few things to keep in mind while relying on standard financial models:

1. Building models purely based on assumptions and past historical events can prove disastrous and leave us unprepared for extreme tail risk events.

2. We must also keep in mind that no finance theory can reduce all the risks to a quantifiable number. A fool-proof model will always account for some amount of uncertainty.

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

EMH states that Markets reflect all the available information and no analysis can unravel new information to help enhance returns. Financial analysis is broadly classified as fundamental and technical analysis. Eugene Fama, a popular economist proposed that neither analysing company’s overall financial information, business motives, etc. (studying fundamentals) nor understanding the historical numbers and charts through some useful ratios (studying technicals) can help one find ways to beat the market. Because, in his view, Markets themselves present all the information that is necessary to generate normal returns and understand inefficiencies.

While the theory is still valid to an extent, Markets are not always efficient. And they do not churn out all the necessary information that are required to enhance returns. In reality, we tend to seek information that we want to know. We are not always the recipients of all the information (also, credible information) available. As a result, the level of accuracy in quantifying risk and correlations are way below 100%. On the flip side, not all information can be factored in. All these attribute to model risk.

This is why building a categorical framework that garners only relevant information about business/stock/company is important. In my view, if you cannot put a piece of information into the framework, then you cannot use it as one of the factors to build or re-balance your portfolio.

Here are some ways to build one:

- Understanding the relevancy of information: How is this going to affect the current/future outlook of the business?

- Identifying the importance: Does this answer most of my doubts about the potential of the underlying company?

- Deducing the subsets: Can my model make do even without this information?

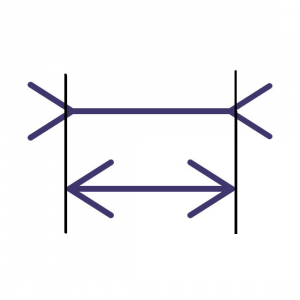

A famous German psychologist Franz Carl Müller-Lyer explained the importance of understanding the difference between our perception and objective reality through his experiment which was later named as ‘Muller-Lyer Illusion’ itself.

According to his experiment, we tend to think that the first line in the image above is lengthier than the second even though two lines are of same the length. You can read more about optical illusions here.

In Finance, this is very common. We usually believe in something based on our past experiences or by finding sources and relationships with information associated with behavioural meaning. Daniel Kahneman explains this type of cognitive bias as, ‘a tendency to believe in What You See Is All There Is’. It is termed as WYSIATI bias among Behavioural scientists.

As investors, we must analyse the fallibility of visual perception with reference to this experiment and constantly analyse ambiguity and incoherent numbers and sharpen our cognitive assets.

Here are some ways to overcome visual illusion:

- Fine-tune your mental framework by further categorising ‘information’ into quantitative vs. qualitative, easily available and not, durable and short-lived, factual information and market reaction.

- Ensure you have your trading/investing story (i.e) investment goals. Every investor has different reasons to become a market participant. Setting up your own story will help you focus on the right amount of information required to manage your portfolio and reduces ambiguity on matters that might otherwise lead to inaccurate interpretations.

Hot-hand fallacy

Another common fallacy where our confidence overtakes reality is Hot-hand fallacy. It is a cognitive bias that explains the Illusion of control quite accurately. Hot-hand fallacy explains how people tend to differentiate portfolio managers/stock pickers as ‘hot’ or ‘cold’ depending on their past performance.

A stock picker is said to be a hot hand in picking stocks that can generate alpha if her portfolio has over-performed in the past. This is a fallacious belief of associating a random, successful, past event to expecting a future, probabilistic event, to be successful too.

Illusion of control is all about the tendency of people to overestimate their ability to control events even when they have no reasonable influence ever. It also relates to the confidence in predicting the event.

The Collapse of Amaranth Advisors is one such example where the firm and its investors saw Brian Hunter as the hot hand and Brian’s illusion of control made him lose large bets that he made against the hurricane. It is, in fact, statistically proven that the higher the illusion of control, the lower the trader’s performance.

Loss aversion

Nobody enjoys losing to someone or something. We have already discussed this in lengths in our previous article, Game theory.

What ‘loss aversion’ tells us is that we hate losing more than we enjoy winning. Yes, read that again and tell me there was not a moment in your investing lifecycle you stopped yourself from buying a stock, after knowing that you have a 50% chance of losing than winning (that’s right, you have the same 50% chance to win). I think not unless you are young, risk-seeking and enjoys the adventurous ride that the Market takes you on.

Loss aversion is said to have an even bigger impact than that on an investor. Behavioural science studies say that people tend to be overly pessimistic about a company/investment when a stock hits an all-time low or has to experience a petty slander with no appropriate base. It is a fallacy where the brain connects to disappointment and suffering more deeply than happiness. Thus, Losses loom larger than gains and we immediately see that as a threat to our entire portfolio.

As a rational being, you should ideally treat every threat as an opportunity to thrive in the market. Reacting adversely to market turbulences will prevent you from chances to recover from losses.

Nearly opposite to this bias is the Endowment effect where you don’t want to give away what you own, simply because you like the idea of owning than having to let go. In your head, the value of a stock is more than what you will receive by selling it.

While it is important to seek opportunities during adverse market situations, it is also important to learn to let go of one, especially when you are being paid the same or more than its original value.

Price confusion & Money illusion

When the price of a commodity falls or rises, we try to look for a pattern. Is it because of Demand? Inflation? Scarcity of raw materials? Increase in manufacturing expenses? Sometimes we even tend to think that it is a fact when the exact opposite is true. It is fundamental to understand that price actions are mathematically random and mentally condition ourselves to withstand Price confusion. Whatever it is, you will anyway have to pay the price of volatility. So, as rational investor, we must keep looking for opportunities to pump out gains elsewhere rather than being trapped in momentary price actions.

Additionally, according to Irving Fisher’s, The Money Illusion, people generally consider wealth in nominal terms and not in real terms. It provides a false sense of security for an individual’s wealth. And, one of the main factors contributing to this bias is not accounting for inflation.

So, it is important to be able to understand the difference between real and nominal prices.

Black Swan

A Black swan event is characterised by an extreme impact that can be explained only after experiencing the entire event. This term was popularised by a famous Wall Street guy, Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Mathematically, one can never have foreseen such a catastrophic event occurring in their list of tail-risk events. An Outlier! The Dotcom bubble was one such event. While this is not an illusion prevailing in the Markets, we cannot treat it like an Invisible Gorilla that nobody pays any attention to.

Investors must allot a percentage of trading capital and stick to it. Trading capital set aside should ideally be a quarter or less than 50% of an individual’s salary. One must ask this to oneself before allocating trading capital – Will I be able to weather the storm upon losing money to an unexpected event?

Always remember, your behaviour with money is important than how intelligent you are, and such a behaviour will be determined by how well you handle your investments!